This week, we’re going back in time. Or should I say, Bach in time, because that is an original joke I just thought of and no one else has. Also, today you’ll be getting two for one – I’m going to make you listen to TWO Baroque pieces you’ve probably heard before.

Like most eras of music, the Baroque era coincided with a wider cultural movement which started in 1600. Baroque architecture popped up in Rome and Italy at this time and was soon adopted all over Europe, especially the Catholic church. People were starting to believe that art should reflect the sacred, and vice versa. So churches started to look like this:

Walking into a Baroque church is like walking into an art museum. Look up, and there’s probably a big ol’ facade with a painting of God (usually depicted as an old white man?) Look around, and there are half-naked saints of antiquity in various dramatic, contorted positions, either in sculpture or in painting. These architects wanted to show they didn’t give an eff about the boring Reformers, who were making plain, boring churches. Baroque artists and architects would spare no expense to make sure things were elegant, aesthetically pleasing, and perfectly designed.

Baroque music took this cue as well. If you’ve listened to any Baroque music at length, you’ll notice that it’s very neat and tidy – every note fits into place (no syncopation because that is SATANIC) and it all resolves with a neat little bow at the end. Baroque composers rarely broke the rules. Like Baroque architects, the composers liked some embellishment and ornamentation, but as long as it had a good place in the music. The music was extravagant, but not overstuffed. This is also where modern opera got its start, and I’ll let you have your own opinion of that.

Enter Bach, the last child born to a German family of mostly musicians. He’s probably one of the most famous composers in the world, which is odd, because he was, by Baroque standards, quite conventional. But he also wrote a heck ton of music. He especially loved the clavier (we call it a piano now – it was a lil different back then) and the ORGAN. Who doesn’t love the organ?

“Little” Fugue in G Minor (I don’t know why “Little” is always in quotes. Is it little? Is it not little? Is it reasonably sized?)

Bach loved the fugue. A fugue is a frequently recurring musical theme that sounds at different points of a piece, usually from a different voice in the orchestra (in this case, it’s the lower and higher voices of the organ.) You can hear the theme established at the very beginning of Little Fugue, and when it’s done, the low voice takes over while the high voice goes off and has a little party on top. Although Bach continues to embellish as he goes on, you can still clearly hear the theme throughout the fugue. Sometimes it’s in its original minor key, other times it’s in a major key for a hot second.

Unlike some of the other music we’ve explored so far, Little Fugue is neither a tone poem nor a progam piece (a piece that’s specifically supposed to mean or represent something.) It’s just a frickin fun piece. And I think it demonstrates the neat and tidyness of Baroque music.

BUT NOW WE’RE GONNA GET CRAZY.

Toccata and Fugue in D Minor (evil laughter in the background)

Seriously, if you’ve never heard this piece, where have you been? Do you hide under a rock every Halloween? The dark tone of this piece lends itself to being a sinister theme for many a villain in popular culture. It’s also a fugue, but the most popular part of this piece is the beginning – the toccata. While it sounds like it could be a type of pasta, it’s actually a fast-moving, lightly fingered, expertly-played piece of music. It’s like Through the Fire and Flames on expert mode. Y’all best be prepared.

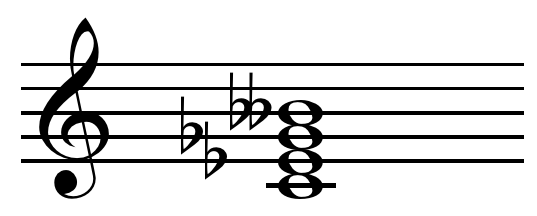

What’s most suprising about this piece to me is that it might have been written by Bach in 1704, when he was still in his teens. The date of this composition is widely debated (it may have been just a few weeks/months before he died). After the dramatic toccata, we are plunged into a very dramatic fugue with lots of dynamic changes. Also, we hear a diminished seventh chord (at about 7:40) which isn’t very kosher for Baroque composers:

The fugue is a bit different from Little Fugue in that in goes through several more tempo changes and is played almost entirely in sixteenth notes. It almost sounds messier than Little Fugue, doesn’t it? Messy might not be the right word, but it almost seems a bit freer of constraints (the last seventeen measures alone go through five tempo changes.) It also ends with what is called a plagal cadence, or the “amen” cadence (if you ever sing a hymn in church and it ends with two huge “AAAAH-MEEEEEN” chords, that’s a plagal cadence.) Except its in a minor key, so it’s a creepy amen cadence, and you are left unsettled but also satisfied by what you just heard. (At least I am.)

If you don’t know how you feel about organ, listen to some organ works by Bach and make up your mind. He certainly gave you a lot to choose from. It might sound Baroque, but don’t fix it.

a. w.