Humans are rebels by nature. If they weren’t, then teenagers wouldn’t come home with piercings in odd places and America would still belong to Britain. Also, if we weren’t such rebels, we wouldn’t have music. At least, we wouldn’t have the incredible diversity of music that we have today.

When you think of rebellion as it relates to music, you probably think of rock n’ roll, don’t you? Elvis and his hips led the way to decades of preteen girls gyrating to their record players, stoners growing their hair to obscene lengths, and rockers ripping up clothes for no particular reason (read: the 80s.) Then rock n’ roll had a bastard child and named it Metal, while somewhere in the background Bob Dylan crooned folk into existence. All of these genres were created because people wanted something different from music. They wanted it to create a new feeling for people to feel when they listened to it.

This rebellion didn’t just start with rock n’ roll, though. Jazz was the original rebel of the 20th Century. Scott Joplin’s ragtime was thought of as being way too sexy for respectable people (and also Satanic, but we’ve talked about this.) A lot of straight-laced Victorian figureheads thought it was leading to the degradation of morals in young people. (Essentially, they were saying syncopation was making teenagers have sex.)

But guess what spawned jazz?

IMPRESSIONISM.

There have been rebels in the music family tree ever since music was a thing (so, pretty much always.) But in my opinion, I think Impressionism played pretty heavily into the evolution of music as we know it now. So let me take you on a journey to explore this very odd spawn of the family tree.

Brandy, you’re a fine girl, but my first love is La Mer: Impressionism and Our Boi Claude Debussy

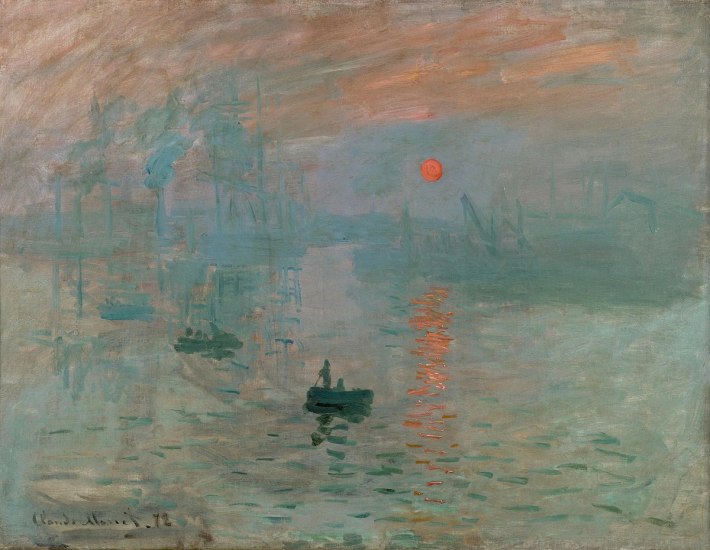

Once there was a French boy named Claude, and he was a hipster. This was the 1890s, the original hipster era. And he was French, the original hipster country. Like a lot of the composers I’ve talked about, Claude Debussy was very dramatic and short-tempered. He went to music school, but immediately stuck out because he played unconventional chords and styles unlike his fellow pupils. This was around the same time Impressionism was coming to its own as an art form. The art form was characterized by its accurate (and striking) use of light and small brush strokes. The painting could be as vague or as specific as the painter wanted it to be.

Debussy sort of accidentally became the frontrunner for Impressionist music. He didn’t like the term and refused to use it when it came to his music, but his music follows closely on the heels of Impressionist art. Just listen to one of Debussy’s famous piano pieces, Clair de Lune. It almost feels spontaneous, like he’s coming up with the chords and melodies as it suits him. That’s kind of the point of Impressionism – it’s not supposed to feel pre-planned, but free-flowing, like the nature it’s inspired by.

And now for La Mer. Oftentimes in literature, the ocean is characterized as a beautiful woman that sailors are fiercely loyal to. (Poets and writers are dramatic, so of course they are going to characterize it this way.) Painters love ocean and water – just refer to Monet’s piece above. If you think about it, Debussy’s La Mer sounds the way we painting looks: ambient chords, sudden bursts of color from the horn section, chromatic scales illustrating the ever-changing temperament of the water.

Music critics have noted that while La Mer is described by Debussy as “three symphonic sketches” instead of simply “symphony,” but it fits well in the symphonic category – the first and third movements are broad and powerful and the middle is fast and upbeat (called a “scherzo.”) The three movements are as follows:

I. From dawn to noon on the sea

II. Play of the waves

III. Dialogue of the wind and the sea

Interestingly enough, Debussy did not spend much time by the sea while he wrote La Mer. He finished it in a hotel in England. He said that he got much of his inspiration for the piece from paintings and literature about the sea. The “sea” we hear in La Mer, as a result, is idealized and romanticized.

La Mer was not super well recieved when it debuted, but that was mostly because the orchestra didn’t rehearse super well and Debussy wasn’t very good at the whole “private life” thing (he had recently divorced his wife in order to shack up with a married woman. Kind of a no-no.) Much like his music, Debussy was spontaneous. He had several lovers during his relatively short life, and the women who lived with him said he was…difficult (and that’s being nice.)

Like I’ve said before, artists are hard to live with. Especially hipster artists. But they can crank out some darn good music, music that influences the way it’s done for decades to come.

And he didn’t even have to gyrate his hips.

a. w.

[…] Classical Crash Course, part five: Things Get Weird (aka Impressionism) […]

LikeLike

[…] Classical Crash Course, part five: Things Get Weird (aka Impressionism) […]

LikeLike